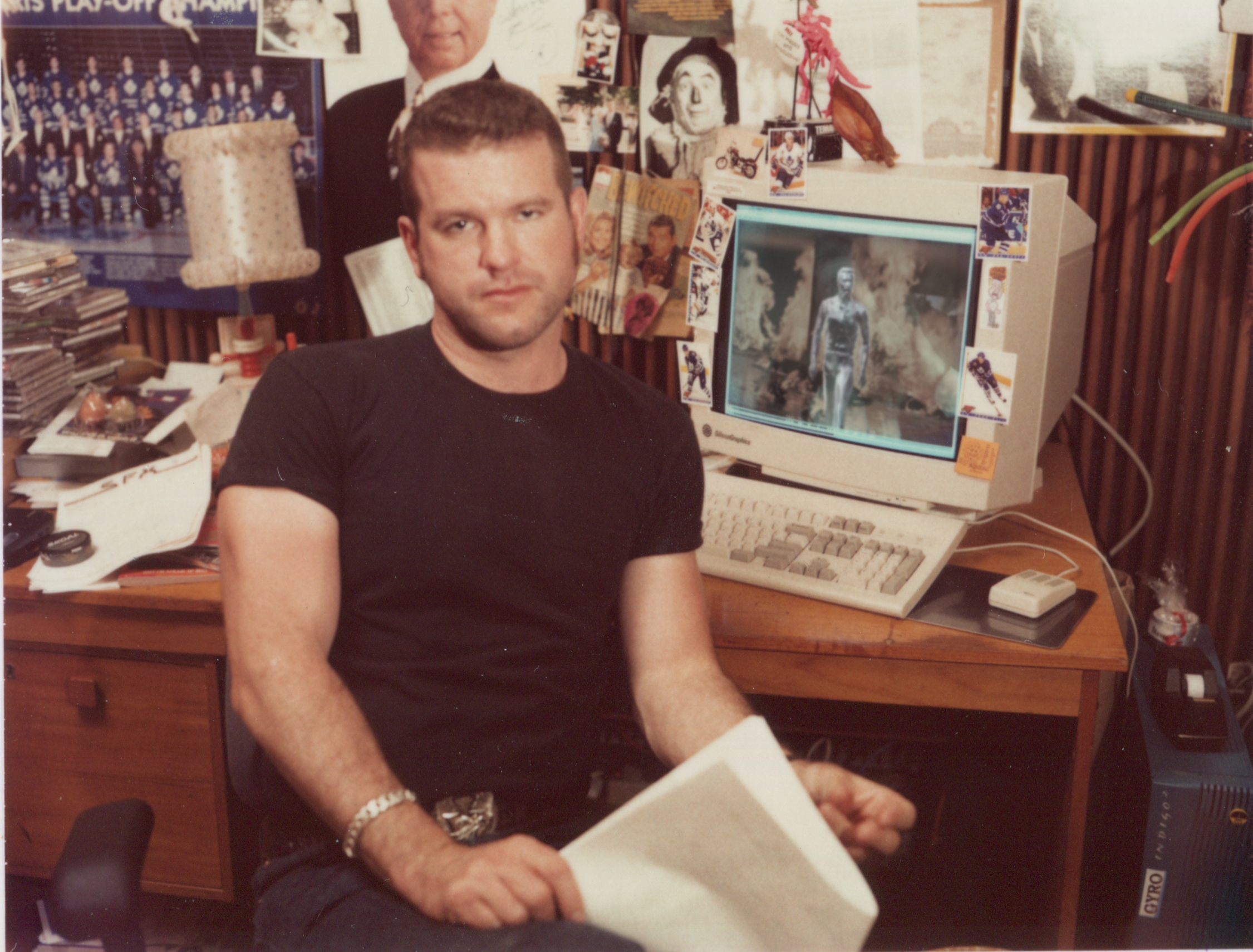

Steve Williams is personally responsible for pioneering one of the greatest changes in Hollywood history thanks to his groundbreaking work in CGI – but it’s unlikely you’ll recognise his name.

However, you have undoubtedly seen – and admired – his work, which ranges from and Terminator 2: Judgement Day to The Mask and Jumanji.

In fact, the 60-year-old Canadian by initially working with visionary filmmaker for 1989’s The Abyss to create that first-of-its-kind photorealistic water tentacle creature that replicates actress Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio’s face – a moment everyone remembers.

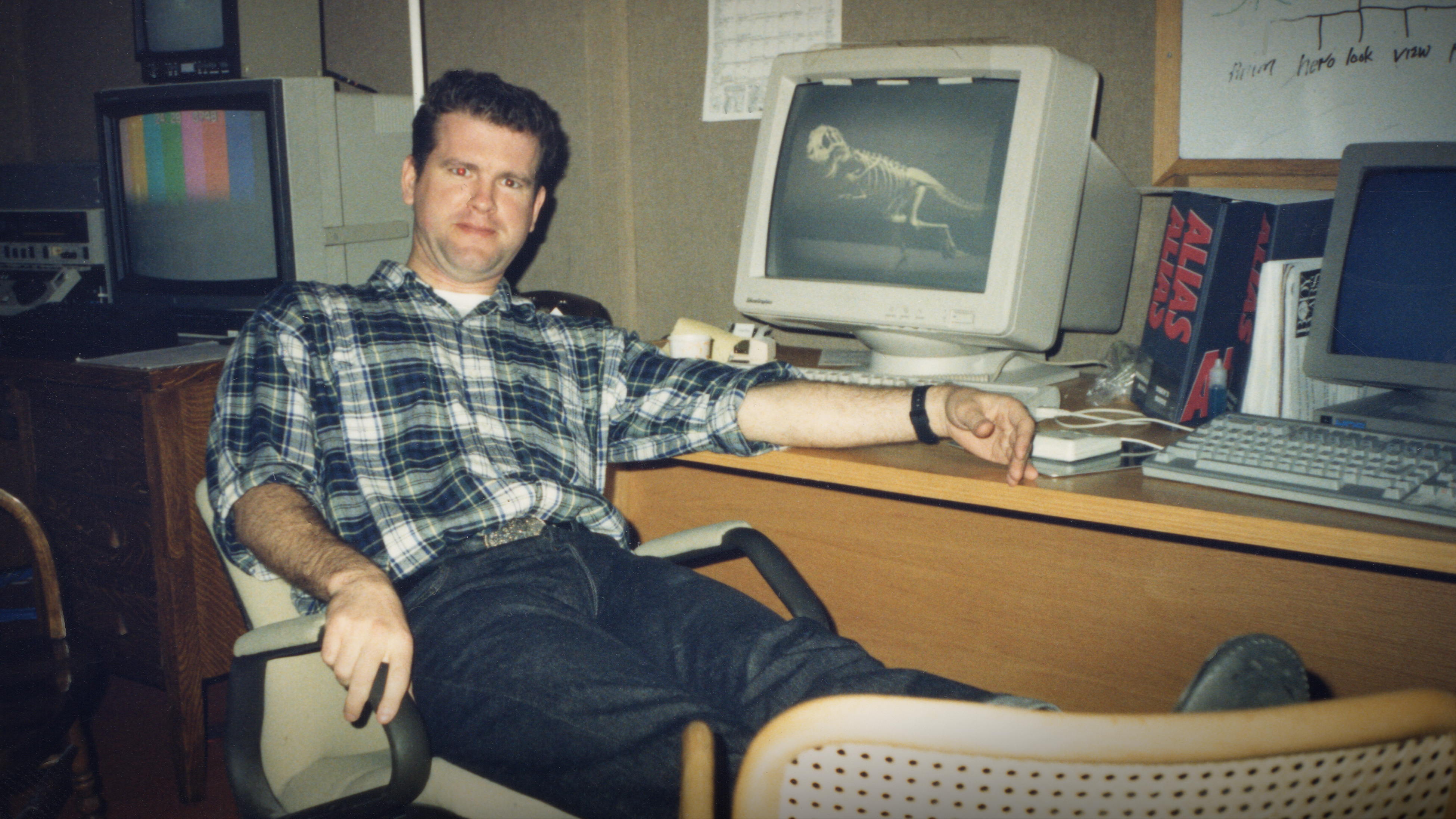

While employed at Industrial Light & Magic in the 1980s and ‘90s he then also toiled away on Terminator 2 and Jurassic Park, pushing computer graphics and visual effects as far as they could go at that time, and certainly beyond what most people thought was possible.

It was him who worked out how to create Robert Patrick’s T-1000, , allowing him to morph into liquid, meld his head back together and walk through fire (as well as grow handy blades out of his arms).

It’s no surprise that, 30 years plus later, the effects in those two movies still impress and inspire film lovers despite how much technology has advanced in other areas.

And audiences are about to finally learn much more about Williams and his invaluable contribution to the early days of CGI thanks to an unflinching new documentary, Jurassic Punk, directed and produced by Scott Leberecht.

One of the reasons Williams has likely failed to become a household name was his attitude – stubborn, wild, resistant to leadership and a little arrogant. He rubbed plenty of important people up the wrong way and ended up fired from ILM (and not at the first time of asking, as George Lucas tried to get him sacked for snooping in his inner sanctum at Skywalker Ranch but Williams was too valuable to James Cameron at the time).

Without him, though, it’s fair to say that both T2 and (especially) Jurassic Park would not have been nearly as impressive, not that he got the public credit when the films won Academy Awards for their special effects.

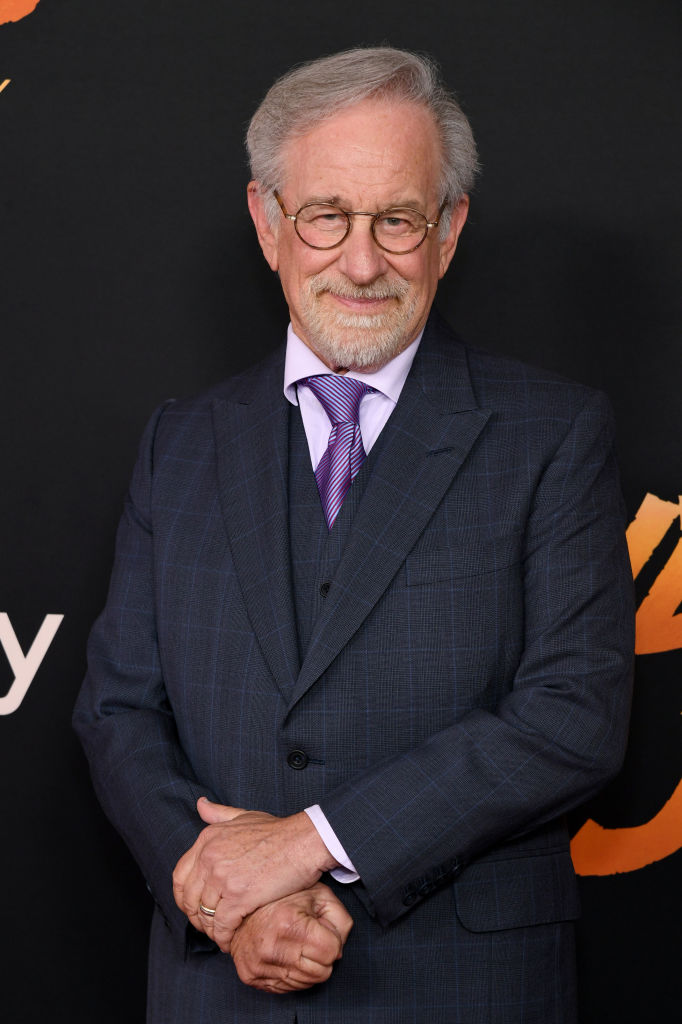

Working in what was termed ‘the Pit’ with his team, Williams (known widely as ‘Spaz’, which is considered a less offensive term in the US) was also far removed from senior leadership most of the time – including director Steven Spielberg.

Despite convincing the world’s most famous filmmaker to change the direction he was initially taking with Jurassic Park – which rather than via CGI when they weren’t animatronics – Williams says that he ‘honestly doesn’t know’ what it’s like working with Spielberg ‘because I never met him’.

‘They just kept me in a basement and pushed food underneath the door,’ he quipped, while talking exclusively to Metro.co.uk.

The team were initially told they were just going to be providing motion blur and nothing else.

‘We were told don’t even bother trying. [ILM senior visual effects supervisor and now consulting creative director] Dennis Muren actually said there’s going to be no computer graphics – and he’s never even touched a keyboard, so he really didn’t know he was talking about,’ Williams added, ego still jostling.

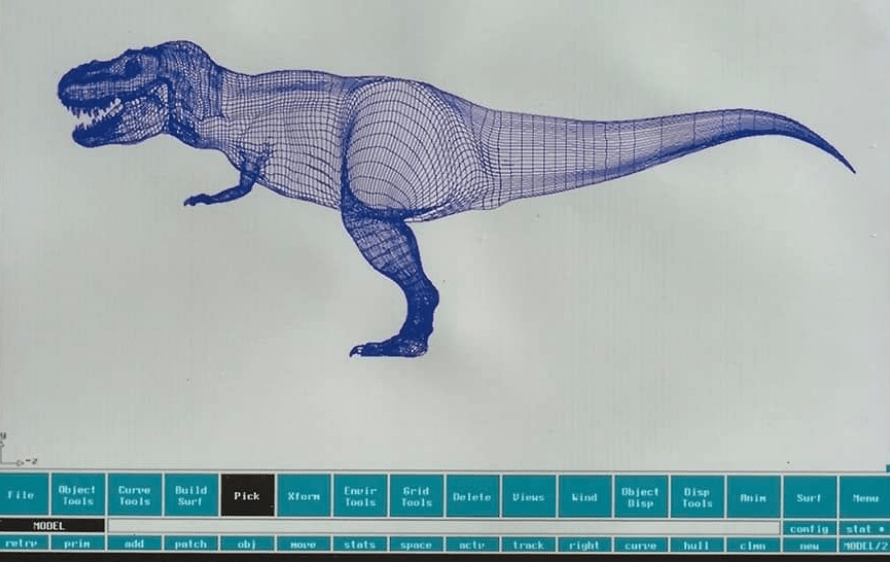

But he didn’t let it deter him from creating what he knew he could, based on his work on Terminator 2 – a fully animated, moving and convincing Tyrannosaurus rex.

‘I secretly built the bones and I ambushed [producers] Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall when they were coming in, and it was the first and only time I ever met her.’

But what they saw was enough to convince them that what Williams was saying he could do could be done.

‘It was approached the way that you would approach a stop-motion movie, although there was this new thing called computer graphic dinosaurs in it, which essentially meant everyone was learning – Dean Cundey the DP, Spielberg too, I gather. He has a very specific storytelling methodology and I think that this threw it for a loop,’ Williams recalled.

One of the key differences was a lot less cheating when it came to cinema angles only hinting at the size of a CGI creation.

‘Like in Jaws, only bits of the creature [were shown] because as a puppet or an armature, it starts to expose itself pretty fast when it’s not working,’ he explained.

‘Or you look at what Ridley Scott did [in Alien] – he never showed you the whole creature, he only showed you bits of the creature, so your imagination is given a job. Jurassic was a deviation because we could stay on a shot for three, four seconds, which is a long time for a full-screen character. It really hits you right between the eyes when you first see the brachiosaurus, because it’s on for a long time.’

Williams is, of course, referring to the start of that incredible vista in the 1993 movie all see a living and breathing dinosaur for the first time, alongside the audience, before the camera pans to show herds of them across the grassland in the distance. It’s one of the most striking sequences of shots in cinema.

Of course, at the time the VFX was rightly fêted, but why now, in the age of CGI cropping up in most movies and being used for more and more fantastical creatures and stunts, are these 30-year-old dinosaurs still so compelling? Why do special effects from this film – and Terminator 2 – seem more convincing, given the advancements in the arena that have taken place?

‘We were using traditional filmmaking techniques and the camera wasn’t moving a lot – now the camera is all over the place to the point where you don’t believe it,’ Williams shared, in the fist part of his response.

The other reason? As Jurassic Park’s dinosaurs were created digitally but the film was distributed on 35mm, ‘we had to add literally film grain to the characters before composite in order to match it’.

That even includes tiny details such as anticipating the anomalies of cameras and projectors in cinemas – whereas sensors in current cameras mean ‘images are so clean that no grain is necessary anymore’ .

Williams likens it to your stomach not being given anything to digest.

‘That also applies to film in that your imagination isn’t really given a job anymore either,’ he explained.

‘There was a purity about that time, 30 years ago, because no one had ever seen anything like that before.’

Williams turns to a 90-year-old film as another example, with the 1933 version of King Kong.

The movie is black and white, but Williams asserts that ‘once you get into it, your brain is filling in the blanks’, rather than being ‘pushed into neutral because everything’s being shovelled to you’.

Another comparison is the rising popularity again of records, as people look for authenticity, which is considered comforting in its little flaws that add realness.

He’s not thrilled, to say the least, at how things have turned out once the success of his VFX breakthroughs was confirmed.

‘Then of course, what do studios do? They said, we’ve got something, let’s do another one and find a bigger creature and, all of a sudden, the antagonist – which is the visual effects – ends up deposing the protagonist – which is the story and the character.

‘We’ve just seen that manifestation gestate over the last 30 years, and I warned about it back then and I got in a lot of trouble – I got in a lot of trouble all the time anyway.

‘I said, “[With] all we’ve done, you’re looking at the beginning of the end of filmmaking” and everyone got really mad at me.’

Williams is technically the man that decided how dinosaurs moved, and certainly the film’s centrepiece, the T-rex, given how the movie is still most people’s immediate reference when it comes to these animals. Audiences had never seen them in motion like this before, and the CGI blended seamlessly with Stan Winston’s first-class animatronics to give a full picture of the beasts.

The special effects expert relied on his background in animation as well as his love of animals, as he tackled what became a ‘personal challenge’ with many late nights in the office.

‘To make nine tons of hydraulics run, it took me four months to figure that out,’ he revealed, as all the traditional techniques he had used before were out the window thanks to the T-rex’s sheer size.

Think on that, next time you’re watching the T-rex pursue Laura Dern and Jeff Goldblum’s jeep, glimpsed in that iconic wing mirror shot.

A big help was that, unlike stop-motion, everything doesn’t have to be done there and then, ‘at the time of camera’ – so Williams spent six whole months working on purely the 375 frames of Terminator 2 that showed the T-1000 walking out of the fire.

He says the technology was ‘like a paint that never dried until we wanted it to’, where everything could be layered on top until it was perfect.

‘I basically built the T-1000 like you build a shirt, and I built the T-rex in exactly the same way, no difference.’

However, this benefit – and the power it gave to keep improving – is part of what Williams sees as the issue.

‘[CGI] sort of displaced one thing but begat another and that’s what the problem is, is that when that tool became so easy to use, then it became overused, which is my criticism. That’s why people go back to the first Jurassic.’

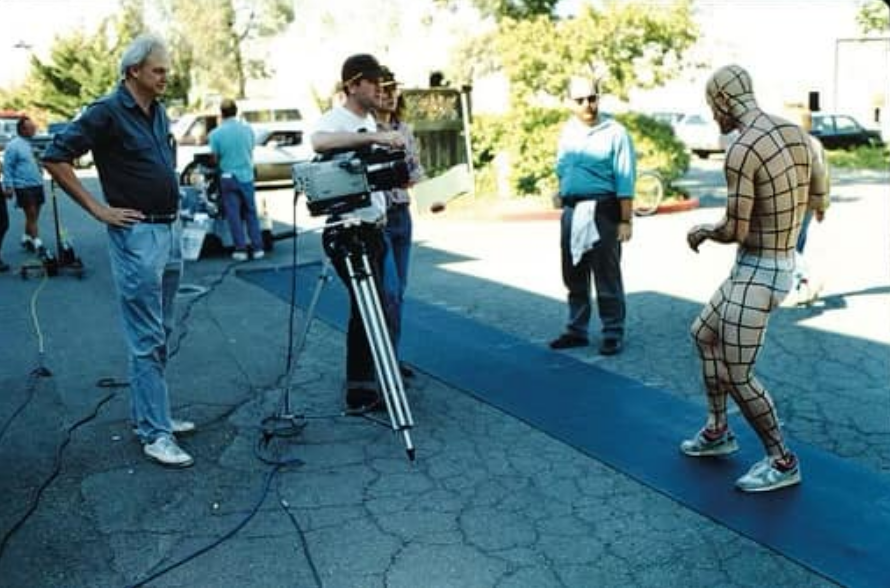

When Williams was first working on his CGI technology, developing it for the T-1000, he had the benefit of being able to work together with actor Robert Patrick, who is still a friend today. In the days before motion capture, Patrick was extensively photographed, filmed and scanned into a computer in sessions which often saw his body drawn all over, marking him up in grids.

Footage in the documentary shows Williams and colleague Mark A.Z. Dippé working together ahead of shooting, figuring out exactly how the T-1000 will move to match Patrick’s performance, which had also been informed by working with an Israeli Defense Forces commando.

‘I was listening the whole time to what Robert was talking about and I knew I had to turn him into a machine yet at the same time it had to have some Hominidae component to it in order to be familiar with the audience,’ Williams said.

His relationship with Cameron – started on The Abyss and continued on Terminator 2 – is closer and more collaborative than that which he had with Spielberg. It appears theirs was much more a meeting of minds, and not just because they are both Canadian.

‘He’s very technical and his background is an engineering, so we hit it off right away,’ the expert revealed.

Williams also regards him as the spark for most of what he achieved in the field of CGI.

‘I considered him a real visionary because, truthfully, had we not done The Abyss and we had not done Terminator, we wouldn’t have done Jurassic Park.’

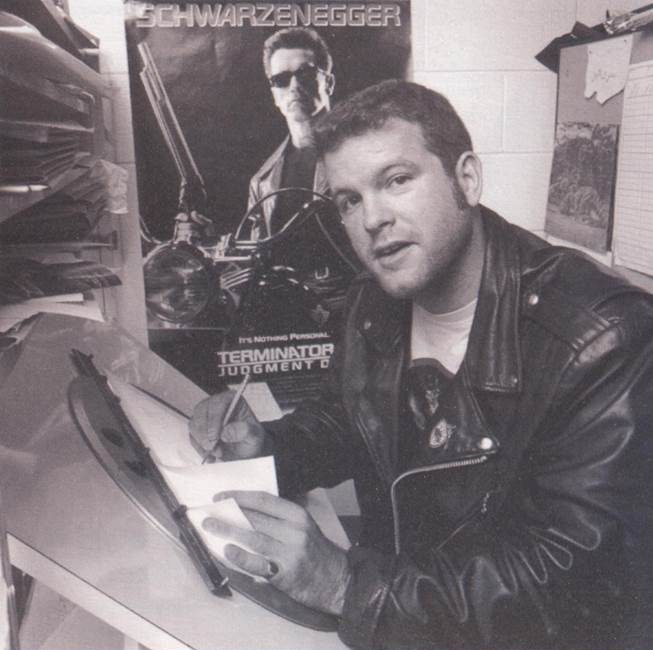

Williams still remembers reading the script for Terminator 2 for the first time, entering a room which held it for his allotted time slot, and being immediately inspired.

‘Even though you’re looking at the simplicity of words, what it does to your mind is that you’re doing technical calculation on trying to execute what you’re reading – and that was Cameron.

‘He pushed things very, very far, and it’s a good thing he did because he was the one that drove us as the pencil makers. His ideas drove those new colours, that new palette.’

Williams also says he shared a two-page document with the Oscar-winning filmmaker years ago, outlining ideas including that of ‘awareness exchange’ and a meeting between synthetic characters and real-life ones – he claims that Cameron later told him he was after reading his musings.

Williams reckons his Canadian upbringing has a lot to do with his approach to his skillset, growing up with the influence of the US (and its TV) right next door, which meant ‘we end up knowing the Americans better than they know themselves’ – and with fewer opportunities.

‘We did not have those types of colours, so we ended up developing really good imaginations. So, when you walk into a scenario where you’re provided with this candy store of colours, you go crazy. I know Cameron is exactly the same way.

‘We didn’t have a lot, and so when you come here, it’s [like] you’re given a credit card and can go blow as much money as you want to, do whatever the hell you want – and they take it for granted.

‘Ironically that’s sort of what’s happened to the film industry as well. [With Jurassic Park] it was a very sort of simple, small movement at that time but it has it is metastasised into this huge thing where it’s lost the direction of its intent.’

Nowadays, after a subsequent move into directing commercials and Disney CG animation The Wild in 2006, Williams has left Hollywood behind.

You can find him in Southern Missouri with his cats for company, drawing, sewing and welding after going ‘very deep into depression and beer’ and coming through a painful divorce.

‘I’ll always work with my hands. I just try and keep things simple – I love my kitty cats, and I suppose this is act three of life, right? So I’m gonna try and keep it untechnical.’

Metro.co.uk contacted ILM and Dennis Muren for comment.

Jurassic Punk is available to buy or rent now on platforms including Amazon, iTunes, Sky Box Office, Virgin Media and YouTube in the UK and Ireland.