If you listen to with episode titles like ‘how to meditate your way to CEO,’ are a fan of and , or the words ‘’ mean anything to you, your algorithm has probably served you at some point.

Shetty, 36, a life coach who built his self-help empire on the premise that he had a spiritual awakening that inspired him to go to India and live as a monk, is arguably the most famous self-help guru in the world.

As if to cementing his A-list status, he even officiated in 2022 after J. Lo became enamoured with his work.

But the seemingly untouchable pinnacle of mental and spiritual health has come under fire recently.

An explosive investigation by has accused Shetty of fabricating a great deal of his famous backstory, plagiarising much of his content, and generally pedalling promises of improved well-being to his millions of fans with very few credentials to back him up.

But why are people pretending to be so surprised? Is Shetty guilty of deception or just clever marketing?

Jay Shetty’s ‘spirituality’ empire

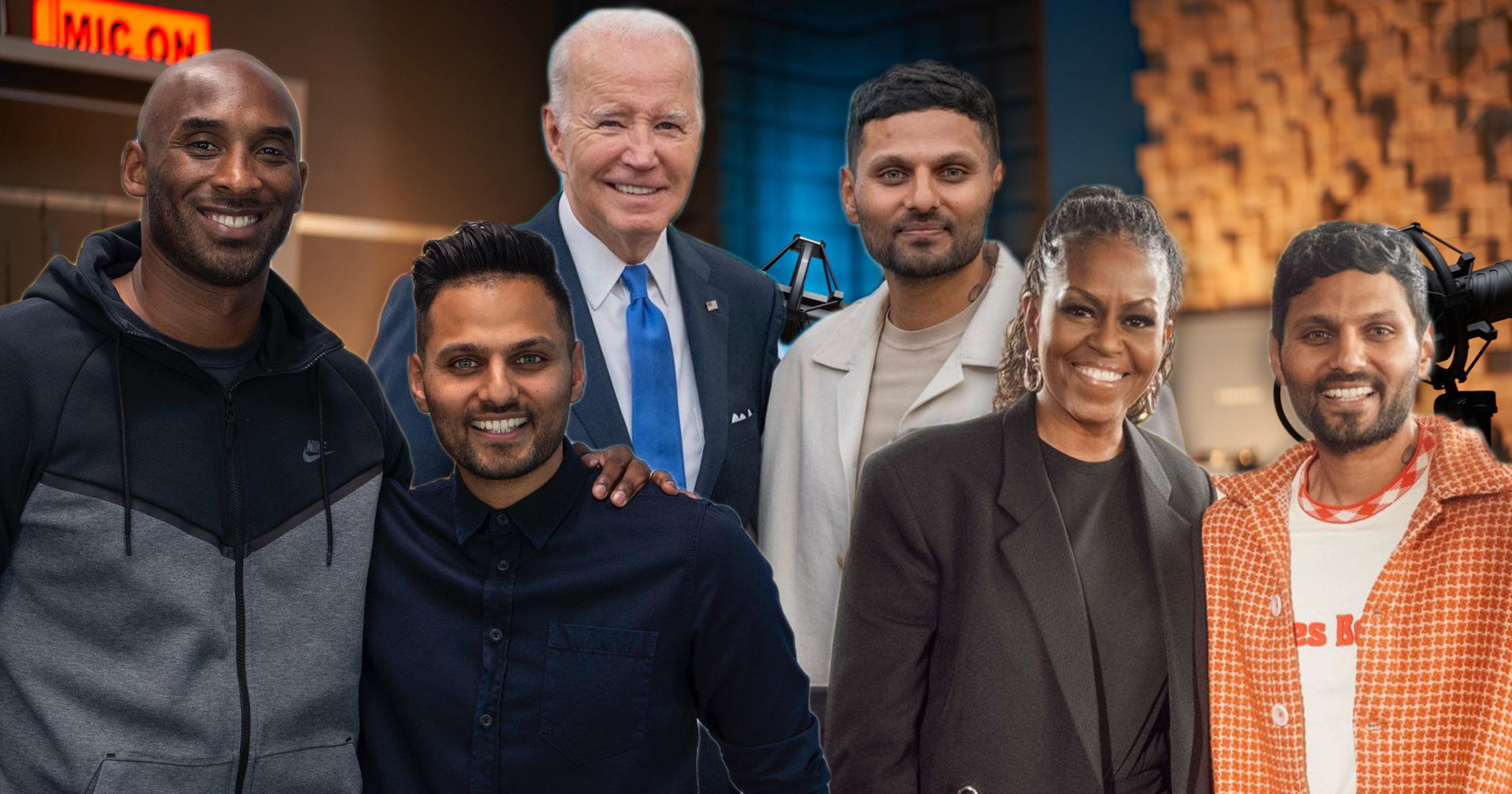

The British-Indian spiritual leader has interviewed everyone from to to on his podcast On Purpose, which was one of the most subscribed-to podcasts in the world last year. Notably, Kobe Bryant granted Shetty one of his final interviews before his death in January 2020. With 14 million followers on and six million spread across his two , Shetty’s face is almost inescapable online.

He’s also a two-time bestselling author, with Think Like A Monk (2020) delving into his experiences studying Hinduism, and 8 Rules Of Love (2023) offering insights for navigating romantic relationships.

Shetty also operates the Jay Shetty Certification School, a life-coaching business where students pay thousands to receive certification as a life coach – one that carries a dubious amount of real-world clout.

Ronald Purser, a professor of business at San Francisco State University, a Buddhist thought leader and the author of McMindfulness, explains Shetty’s appeal as a symptom of capitalism’s tendency to make everything marketable and easy to advertise.

‘A savvy influencer like Shetty, with gobs of charisma, charm and entrepreneurial flair, offers exactly what the masses want – a spiritual-but-not religious, DIY, quick-fix type of “McSpirituality,”‘ Purser writes.

Fraud, or just good marketing?

The Guardian feature takes specific issue with the haziness around Shetty’s claims that he lived with monks in the early 2010s, citing claims from ex-girlfriends and others who knew him at the time of his personal spiritual revolution, that Shetty actually spent very little time in India but was instead making YouTube videos in London throughout much of that period.

‘He went to India probably once during that year and a half that I was in a relationship with him, and that was probably for two weeks,’ an ex of Shetty’s claimed. ‘I saw him in sweatpants more than I saw him in robes,’ said a man who was a monk in London at the same time as Shetty.

These testaments make it difficult to believe the narrative Shetty has shaped across countless talk show spots and other public appearances, in which he claims he emerged from monastic life in 2013 and was so far removed from the ‘material world’ that, ‘I didn’t know who the prime minister was, I didn’t know who won the World Cup.’

But Shetty never claimed to spend the entirety of that time in India. Indeed, he writes in the intro to his first book that he spent that time ‘across India, the UK, and Europe.’ Can he be accused of exaggeration? Sure. But isn’t that just good PR?

Shetty was first the subject of controversy in 2019 when influencer Nicole Arbour published the video , which alleged that Shetty had built his social media following by taking content from smaller creators verbatim and repackaging it for his followers.

Arbour said these creators ‘sent email after email begging him to take [his posts] down or at least credit them, and he just didn’t’. Undeniably true in at least several instances, Shetty responded to the viral video by beginning to credit the people he takes content from, although he reportedly still does so without permission.

Other allegations in the Guardian piece include implications that Shetty’s life coach accreditation program is little more than a multi-level marketing scheme and that Shetty routinely speaks as an expert on issues of mental health despite his lack of qualifications.

Jay Shetty is exactly what he appears to be

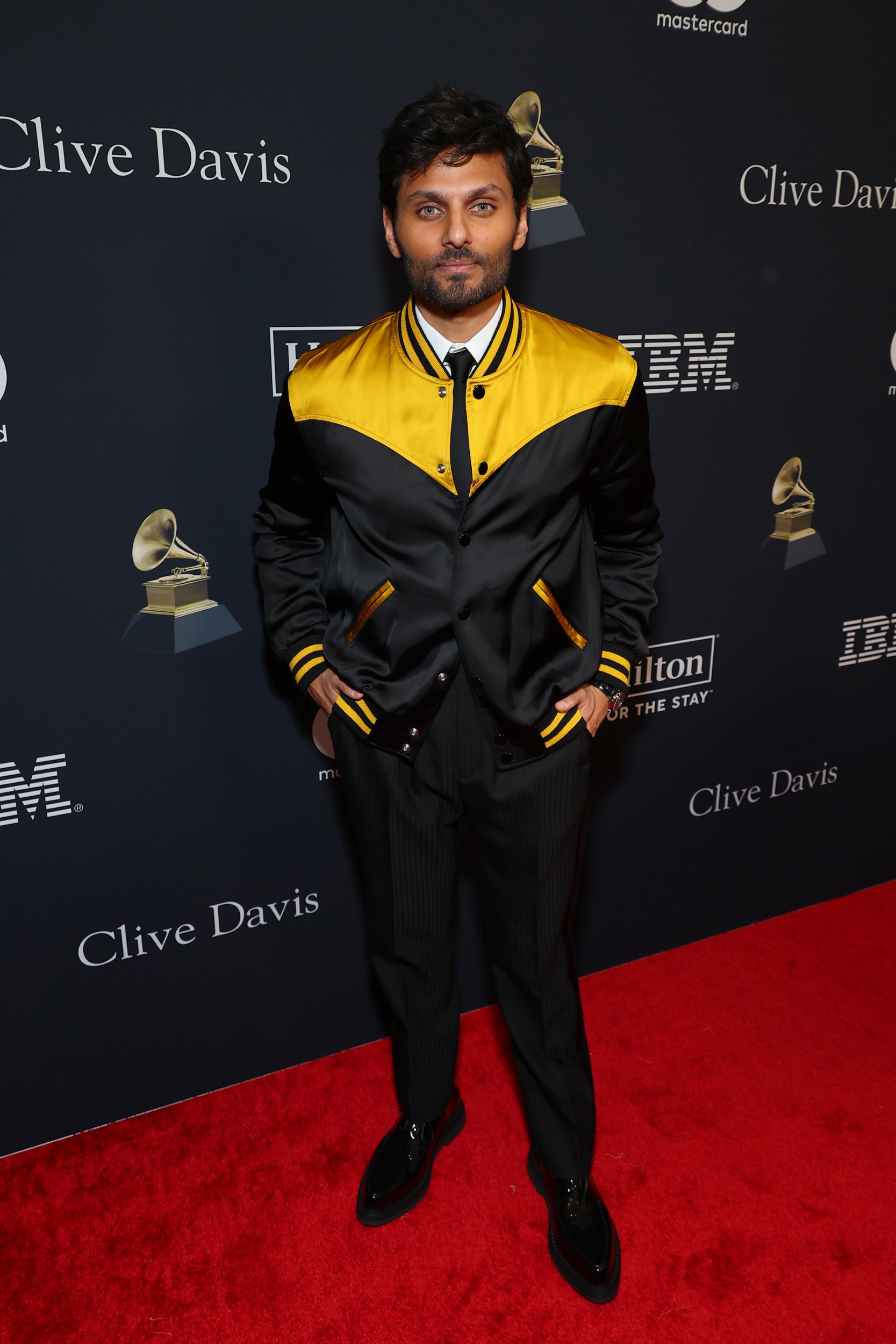

Even if you’ve never intentionally sought out Jay Shetty’s content, there’s a good chance you would recognise him. Undeniably handsome, with green eyes and a movie star smile, the self-help guru’s most common video format depicts him looking directly into the camera and firing off inspirational quotes.

When a little critical thinking is applied to the content of the admittedly appealing videos, they begin to sound like a college freshman who took exactly one intro-level class in philosophy, religion, and psychology. Shetty charismatically spouts off a stream-of-consciousness litany of greeting card-style affirmations that mix the three disciplines in ways that often boil down to little more than word association. Indeed, many of Shetty’s quotes wouldn’t look out of place beside the TK Maxx Live Laugh Love sign in your mum’s kitchen.

But that’s exactly why people connect with him. He’s got just enough genuine affiliation with religion to offer a sense of shaman-like expertise while being secular enough (not to mention comfortingly Western for many) to appeal to the largely non-religious hoards of people seeking ‘personal growth’ and ‘spiritual connectedness.’

There’s nothing inherently wrong with Shetty’s intention to make spiritual and pop-psychology teachings accessible to everyone, which he claims was the calling that caused him to give up his place among the monks.

But when one looks closely at Shetty’s persona and his vast amount of content, it’s difficult not to conclude that the vagueness of Shetty’s backstory is reflective of a vagueness in all of his content. He deals in aphorisms that carry the kind of appeal that horoscopes do: his advice is so general it is inevitably applicable to everyone and is easily digested in the length of time it takes to watch an Instagram reel.

For a guru who aims to serve the world with bite-sized wisdom that doesn’t require any true intellectual engagement or even very much time, it makes sense that he would also reduce his backstory into something equally digestible.

As for his repurposing of other’s content, what platform can truly claim 100% originality? While there’s no excuse for blatant plagiarism, the syndication of content is, if we’re being honest, what runs the ceaseless content grinder of the Internet. And people eat it up.

The Jay Shetty Certification School, for its part, while not necessarily offering legitimate credentials to students in the way an MA program might, has received rave reviews from students, many of whom claim it was life-changing and very genuinely launched their careers as life coaches.

Does it advertise itself with a level of ambiguity that may lead one to believe it is more legitimate than it is? Yes. But is it outright deceitful? No, not any more than any other educational institution that offers promises of a ‘hugely improved life’ in capital letters while hiding its price tag in the small print.

Shetty writes in his book that it was one life-changing interaction with a monk (that he’s said on separate occasions happened when he was 18, 19, 20, or 21, casting doubt on the story) that inspired him to turn to a life of spirituality. He writes in the intro to his first book that this was the first time he met someone who intentionally went from ‘riches to rags’ instead of the other way around, a rejection of materiality that he claims is in alignment with his most core values. Shetty bought a house for $8.4 million (approx £6.6 million) in 2021, an obvious contradiction of his own message and something that anyone with a working knowledge of Google could find out.

Perhaps the question worth asking is not whether Jay Shetty is deceptive and fraudulent, but why we’re still pretending to be surprised by the deceit inherent in successful branding.

None of the revelations in the new exposé are particularly shocking. What is shocking is that we ceaselessly bolster figures who offer obviously too-good-to-be-true promises of inner peace and whose own lifestyles contradict their message.

Shetty has not commented on the story but has continued to post his usual content across his social media channels, including one infographic that reads: ‘You will never see how toxic someone is until you breathe fresher air.’ The sentiment is attributed in small text to another content creator.

Metro contacted Jay Shetty and his team for comment but are yet to receive a response.