Picture it: Simon Amstell is 13 years old, wearing a colourful waistcoat and trying stand-up for the first time.

He’s saying ‘ladies and gentlemen’ a lot, probably because Ben Elton is one of the many comics he’s been watching on the telly, from where he has nicked some of his material.

‘I love that kid now,’ he says. ‘I used to be embarrassed about him. Now I think, “Thank goodness he did that.”’

The Essex drama club he was part of needed something to happen in front of the curtain for a few minutes at their annual variety show while the dancers changed into their tap shoes, so he volunteered to do some comedy. ‘I loved it,’ he recalls with a wide smile. ‘I loved hearing people laughing.’

And now, 30 years later, Amstell has come to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe on a whim, doing a work-in-progress show for a week or so.

You won’t find him in the printed brochure (you’re supposed to make a decision about coming in the spring if you want to be included), but there are a few pretty posters about town to whet punters’ interest.

Nothing about this show is fully formed yet, so when I ask what he’ll be talking about, he gets out a note to remind himself of some themes he’s been considering.

‘The general areas are sex, love, fame, finding peace, trauma, shame, gratitude, ageing, dying, the drama of making films, magic mushrooms, God, healing, meditation, dancing, beauty,’ he says, before releasing a distinctive, high-pitched laugh that makes people around us glance over in recognition.

Given Simon’s track record of doing confessional comedy, they all look like fertile territory for intriguing material.

Following his well-documented experiences of rites involving the hallucinogenic substance, ayahuasca, in Peru (he talks about it on Adam Buxton’s podcast if you want to know more), he’s been doing similar ceremonies with magic mushrooms.

He has a lot to say about the healing properties of mushrooms, and how he feels that when you take them with a specific intention and the correct approach – respect and gratitude – you can learn the ‘difference between all the nonsense your mind keeps telling you is true and the actual truth’.

He feels certain these type of drugs will eventually become legalised for the treatment of depression and anxiety.

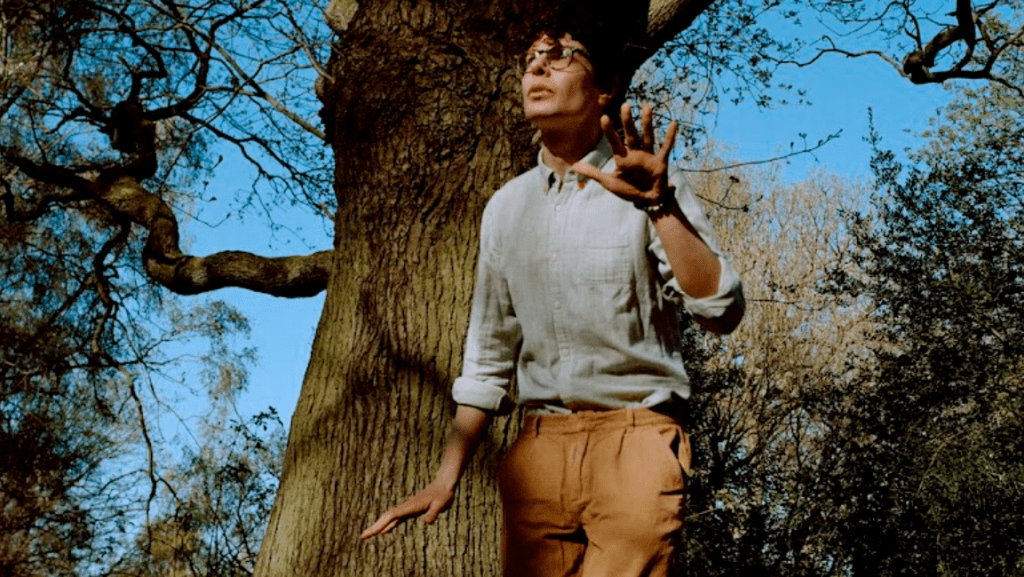

The Simon Amstell you see now has changed a lot since the days of Popworld and Never Mind the Buzzcocks – though the bouncy curls, fresh skin and instinct for mischief are still in evidence.

Since then, he’s written and directed a bittersweet rom-com (Benjamin), as well as Carnage, a hard-hitting drama set in a future in which everyone is vegan (as he is).

He was also written (with Dan Swimmer) and starred in the wonderful series, Grandma’s House, written a book (Help), and done several acclaimed stand-up tours, picking up a bunch of awards along the way.

What’s changed as he takes to the stage now is that he’s doing it purely for the love of it, rather than for any psychological reasons (turns out the adulation of fans doesn’t always fill those holes) or because he needs to get elsewhere professionally.

‘Before, it was really tangled up with trauma,’ he explains of the early part of his stand-up career, when wrestling with his identity, anxiety and residual shame about his sexuality manifested itself in his material and delivery.

‘It’s much for fun for people in the audience now as well because I’m not so desperate for their love. I accept that it’s a night out for people.

‘I still want to make people laugh – that’s the point of it – but the craving for acceptance isn’t there any more,’ he adds. ‘It’s about connection, more than anything else.

‘Often, the thing I’m saying feels a bit like a weird thought that only I am having at first and maybe I’m a bit embarrassed or ashamed to say it out loud. Then I say it out loud and people get it because they feel it too in some way. You hope that fear and loneliness dissipates for everyone in the room.’

His approach to work-in-progress shows is to speak freely on the topics he’s been thinking about, and the following day to listen back to recordings to get a better feel for what felt new and interesting.

He used to try to take notes on stage but that takes too long and he says his handwriting’s too bad. He then plays with the structure and, if he feels it’s strong enough, will consider another tour.

Although he didn’t entirely get on well at Philippe Gaulier’s famous clown course in Paris in his late 20s (‘He drove me nuts’), he did come away with an understanding that comedy means so much more to everyone when joy and vulnerability are at its heart.

So how do you explore the latter when you’re very happy with your life – as Amstell, 11 years into a stable, loving relationship – now is?

‘By the rules of conventional comedy this [joy] shouldn’t really be a funny bit,’ he says.

‘But I don’t need distraction from my own life. It’s very freeing. You’re on stage because you want to be there, and when I’m in the audience I want the person on stage to want to be there – for us all to feel the joy and vulnerability.’

Simon Amstell: Work in Progress, until Aug ,