and in Europe; it was not supposed to be this way.

The defining images of these years should have been shots of footballers in sky blue shirts wearing beaming grins and lauding a gorgeous two-handled shiny silver trophy around an enormous stadium on the continent in front of adoring fans, throwing their superhero coach into the air amid the confetti, the fireworks and the champagne.

It should have been Guardiola as the vanguard of the world’s most talented squad, football’s Harlem Globetrotters, marching them towards glory by maiming the historic battalions who had gatekept the European Cup for too long.

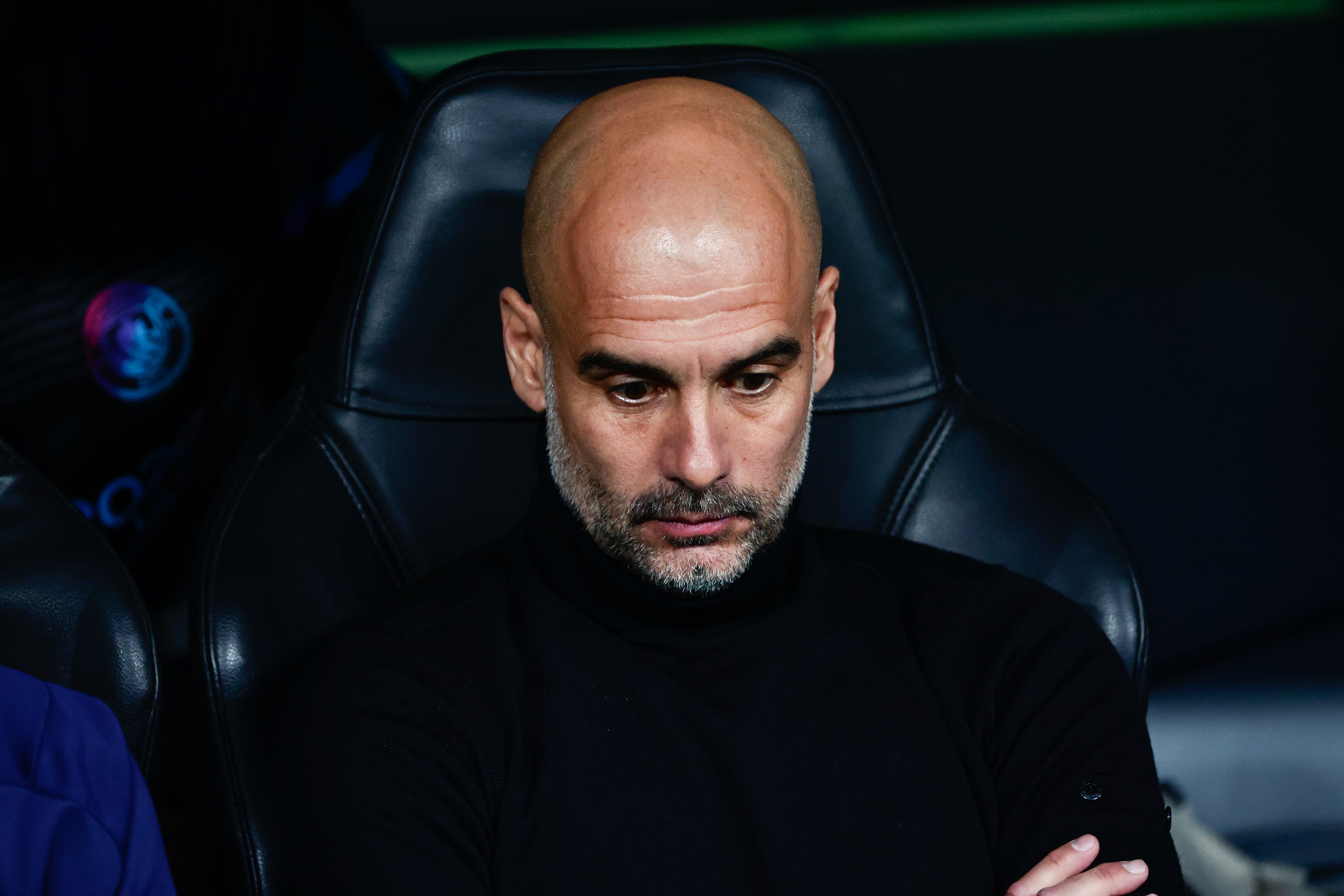

Instead, six years down the line, all that Manchester City have to show for playing in Europe is a flipbook reel of long lens photos with Guardiola rendered prostrate, head-in-hands, mouth agape, pleading towards the heavens without any of the answers.

With only stoppage-time left to play at the Estadio Santiago Bernabeu on Wednesday evening, Guardiola and City had ruthlessly executed their gameplan, and earned themselves a shot at beating Liverpool in a Parisian final which this era of football has been building up to for years.

Six minutes later and Manchester City had been turned over, again, conspiring to throw all their hard work and efficiency away against an objectively inferior football team in six minutes of self-inflicted chaos.

Real Madrid had once again managed what had brought them so far in the competition already — unleashing the very best of their quality, harnessing the power of their home crowd, and the sheer irrepressible energy of the world’s greatest footballer right now, Karim Benzema, to turn a seemingly impossible dream into reality.

If this were a one-off for the away side, an inexplicable collapse in the face of mystical force against a team simply too good to hold back, then Guardiola and City could be forgiven. But that is not the case, because this is a pattern which underpins their shared history and Guardiola’s own failure in the Champions League across more than a decade.

Since winning the second of his two European Cups with Barcelona in 2011, Guardiola has managed Bayern Munich in three campaigns and Manchester City in six. A sole final reached in that period, having built utterly excellent teams capable of pulverising the opposition week-by-week across the course of entire league campaigns, is nothing short of a dreadful return.

In that time, Guardiola has been knocked out of the tournament predominantly because of short periods in ties where his side has conceded a fatal glut of goals. In total, across the 2014, 2015, 2017, 2019, 2020, and 2022 editions of the Champions League, his teams have conceded 18 goals conceded in 79 minutes of football. One every four-and-a-half minutes. Knocked out six times in capitulations, one and all.

If a metaphysical power exists which means some football clubs are simply built for the European Cup, then a final in Paris between Real Madrid and Liverpool is a better than example than one could produce by design. But using ‘the football Gods’ as an excuse does nothing other than justify what, given the sheer scale of the money spent by City on an annual conveyor belt of the world’s best footballers, and their ruthless domination of domestic competitions throughout Guardiola’s otherwise glorious time in charge, is unquestionably a massive underachievement.

That efficiency, that control, which City have so often been able to harness under Guardiola in England simply dissipates in key moments when they play in the latter stages of European competition. The footballers are the same and the sticks don’t move, but the psychology and context of playing in the Champions League, with the show, the music and the whistling, seem to crack the forcefield City have so carefully and brilliantly built around themselves.

None of that is to say that the scale of Guardiola’s influence on football should be challenged or diminished. While still in his late 30s he had become one the greatest and most revolutionary football coaches the sport has ever seen, and his ability to reinvent his teams across micro-eras is testament to his refusal to believe in a single way of winning football matches.

Even the majority of the great coaches are often only able to succeed at the very top level of football for a single generation of playing style. So many see the game pass them by as sports science advances, or their best players retire, or the industry around the game becomes too tiresome. But Guardiola’s City could hardly be realistically more different than his tiki taka Barcelona team which conquered the world.

No matter what happens between now and the time Pep Guardiola leaves Manchester City, he will have changed both English and European football forever. But if there is to be no photograph of him raising the biggest trophy in club football aloft with billowing blue and white ribbons in the next few years, then the scrapbook cover can only be his anguish

, .

, and .