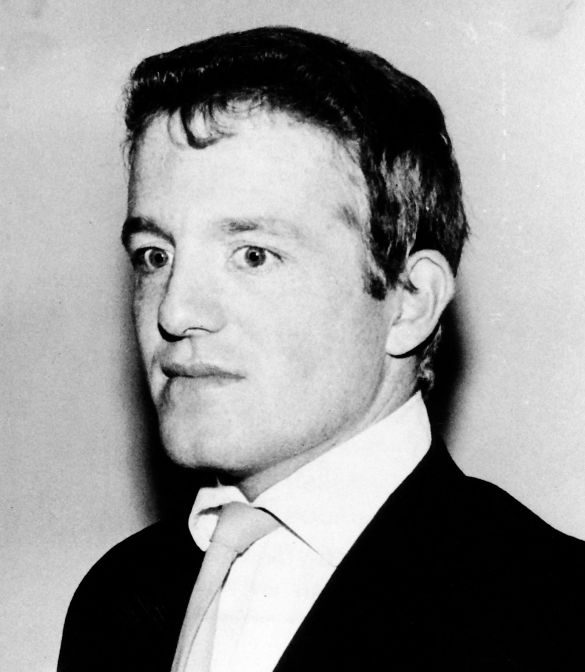

James Hanratty went to his grave known as the notorious ‘A6 Murderer’. Convicted of killing Michael Gregsten and shooting his lover Valerie Storie in 1961, he became one of the last people in British history to be hanged by the state.

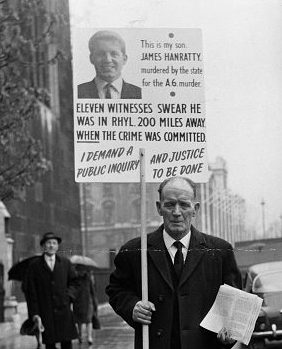

The dark legacy and stigma of his conviction has impacted his family for more than 50 years. However, James’ nephew Darren Hanratty insists his uncle is innocent.

‘There is no shame, yet it has hurt all of us. People call him a mass murderer, a serial killer, but that is just people’s stupidity, he tells Metro. ‘We hold our heads up high. My uncle was innocent. He was framed.’

Plumber Darren has been campaigning to clear the Hanratty name for most of his life.

‘From a young age I always knew I had to get involved. My father passed the responsibility onto me, he trained me up and if justice doesn’t come in my lifetime, my son Frankie has also taken a great interest,’ explains the 56-year-old. ‘We will keep it going. One day the truth will come out. It always does. I have a great sense of injustice.’

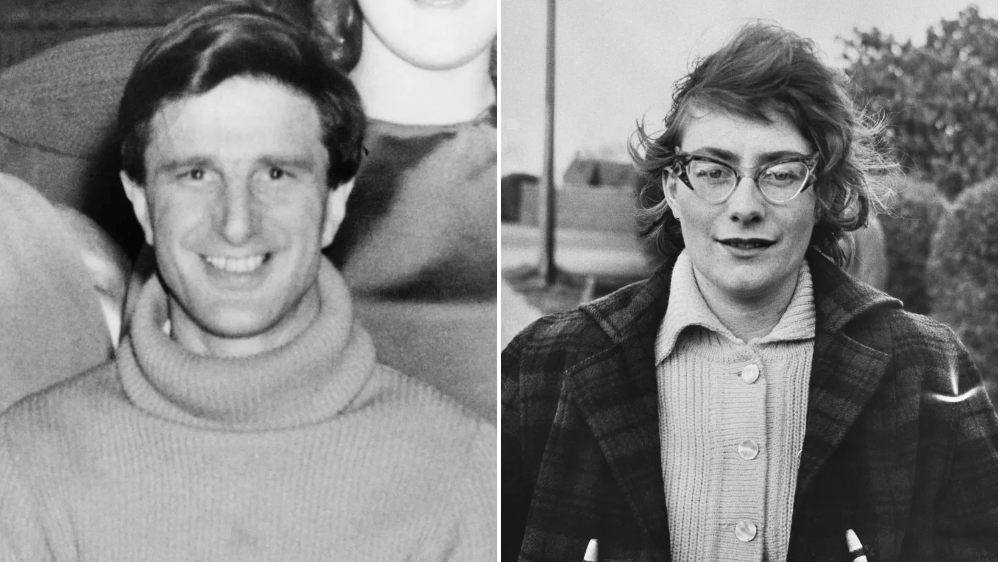

The A6 murder and subsequent trial shocked a generation. On the evening of August 22, 1961, a grey four-door 1956 Morris Minor was parked by a field near Slough.Inside was 36-year-old Michael Gregsten and his girlfriend Valerie Storie.

A ‘desperate man’ approached the car and tapped on the window.

When Gregsten wound it down, a gun was thrust into his face, and the man told the couple that he had been on the run for four months. If they did as he asked, they would be okay.

The man then got into the car and told Michael to drive off.

After 30 miles Gregsten was ordered to pull into a lay-by at Clophill in Bedfordshire. He would be shot twice in the back of the head by the murderer, who then raped Valerie at gunpoint. After, he shot her multiple times, left her for dead, and made off.

Early the next morning a young man discovered the couple and alerted a farm labourer, who called an ambulance. Valerie was rushed to hospital where she received emergency surgery; her life was saved but she was paralysed from the waist down for the rest of her life.

Meanwhile, a manhunt ensued. Valerie gave the police a description of a man with ‘icy blue, saucer-like eyes’, but the police later released a description of a man with brown eyes. It was to be the first of many discrepancies that would dog the case.

An identikit picture was constructed from Valerie’s description, but as this differed from other descriptions provided by other witnesses, two pictures were issued.

Two weeks later, two bullet casings were found in a hotel room occupied on the night before the murder by Mr J Ryan – an alias used by convicted car thief James Hanratty. The room had also been occupied by a man called Peter Louis Alphon, who the police named as the murder suspect.

Alphon turned himself in and was interrogated, but Valerie did not pick him out of an identity parade, and he was later released.

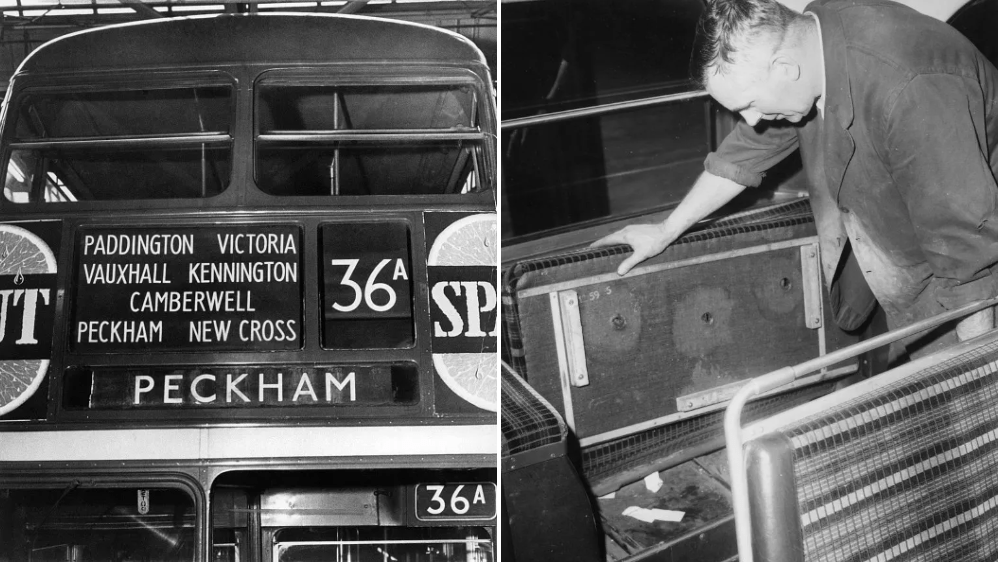

Then in August, the murder weapon, a .38 revolver, was discovered under the back seat of a 36A London bus, fully loaded and wiped clean of fingerprints, wrapped in a handkerchief.

The police turned their efforts into locating Hanratty, who was arrested in Blackpool on 11 October. Three days later, Valerie Storie picked him out of an identity parade and he was sent for trial.

The process divided the British public, who knew that if he was found guilty he would hang.

At 21-days, the trial was at the time the longest in British history and in February 1962 Hanratty was found guilty of murder. In March he lost his appeal and was sentenced to death.

The night before he died, Hanratty told his father that he didn’t commit the murder, telling him: ‘Dad, tomorrow morning I shall take this like a man, but they’ve pinned this on to me’, and asked that the family clear his name.

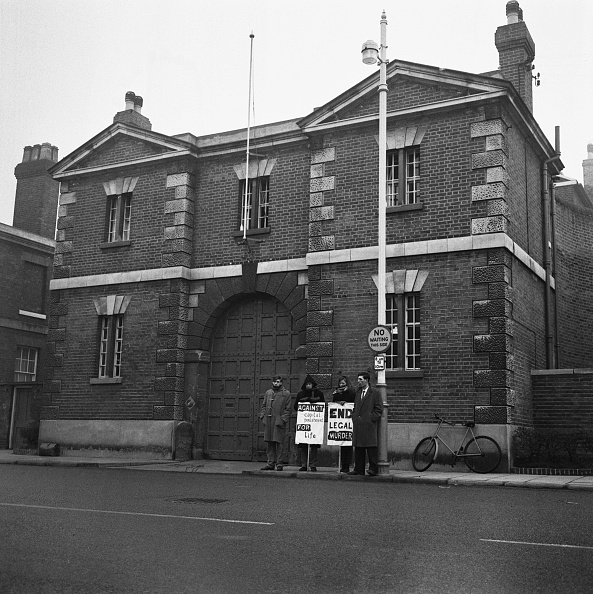

James Hanratty was hanged at Bedford Prison on April 4, 1962. He was 25.

Following his death, many questions remain unanswered. Why did Alphon later admit to the crime? Why did a sweetshop owner in Liverpool, more than 150 miles away, confirm that she spoke to Hanratty just before the murder? Why were the public told the killer had blue eyes, then brown? Why did multiple witnesses place him in Rhyl the day after the murder? Why did a landlady confirm that she let him stay in her B&B on the night of the killing, before switching her evidence in court and then changing her mind again?

Hanratty’s family and friends launched a public campaign to clear his name which attracted a groundswell of support – with even Beatle John Lennon signing up – and four years after Hanratty hung, Darren was born to his brother, Mick.

Darren, from St Leonards, Sussex, tells Metro.co.uk: ‘I never met my uncle, but I felt like I knew him. There isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t think about the case. When my dad was alive, there wasn’t a day that we wouldn’t sit down and talk about it.’

The family would turn the stones over and over, examining discrepancies and points that didn’t add up.

‘It was a terrible crime, but more people believe he didn’t do it than believe he did,’ Darren says. ‘We got more sympathy than anything. Especially from the older generation. I went to a funeral a few months ago and there was a lady there and she said to me: “That was terrible, what they did to that Irish boy. Everyone had pictures of him out.” It is nice to get that response.’

Darren has taken on the mantle from his father, Mick, in the fight to clear his uncle’s name. He even stood at Hanratty’s graveside the damp and chilly morning in 2001 when his body was exhumed for testing.

Two years earlier, following repeated calls from the family for further inquiries into the case, the Criminal Cases Review Commission announced that it was to be referred back to the Court of Criminal Appeal.

The court would then decide whether to quash Hanratty’s conviction, or let the conviction stand.

On March 22, 2001, James Hanratty’s remains, which by then had been moved from Bedford prison to a cemetery near Bushey in Hertfordshire, were exhumed so that a DNA sample could be taken for analysis.

Darren remembers: ‘When Jimmy’s body had to be exhumed, I didn’t want my dad to go through with that. So I was present there in the tent. I had great support from [priest] Father Peter.

‘Seeing something like that; I knew I was letting myself in for and I knew that there would be repercussions, sleepless nights and things like that. It was nothing I couldn’t handle. I’m so glad that I didn’t put my dad through that.

‘The exhumation was done at dawn. The tent was erected, the press were nearby. The grave diggers were there and they had so much respect.’

Jimmy’s aunt had been buried on top of him, so her coffin had to be moved. Then Darren was warned that due to movement and water underground, there could be destruction to the coffin.

‘What happened then will stick in my head forever. They lifted up the coffin from my aunty Annie and the gravedigger warned us that there could be a suction noise. There was a chance that the coffin could collapse or deteriorate in the mud. He got down to my uncle’s coffin and they scraped it, said: “We’ve got something here” and he brushed at the brass cross on the coffin, which shone like it had just come out of the shop. The cross was just so bright. I was thinking; “Jimmy knows what’s going on”. It was just unreal.’

The coffin was taken away in an ambulance so the body could be tested, and a optimistic Darren believed that DNA testing would at last prove his innocence.

However, the family did not get the results they had hoped for.

The DNA sample extracted from Hanratty’s exhumed body was matched by forensic experts to two samples from the crime scene and in May the following year, the Court of Criminal Appeal ruled that Hanratty’s conviction was sound and that there were no grounds for a posthumous pardon.

‘It was like we’d won the lottery, when we’d originally heard about the testing,’ recalls Darren. ‘We were so looking forward to it. DNA testing was a new thing then. We thought, one way or the other the truth will out.

‘But the testing was done in a way that wouldn’t have stood today. So when the result came through, it was terrible. With all the evidence that Jimmy didn’t do it; it just didn’t make sense. There was something wrong with the science; it was contaminated.’

From Darren’s point of view, the way the evidence was stored and handled compromised it.

‘The exhibits were all kept in the same box and passed around the jury. The handkerchief wrapped around the gun, we’re not denying that that is my uncle’s handkerchief but he didn’t wrap that gun with the handkerchief,’ he says.

‘That gun was there to be found. If you had committed a crime like that, that gun is going into a river or somewhere never to be found. Not wrapped in your own handkerchief. And as far as the DNA that was found on Valerie Storie’s underwear; that was contamination, 100%.’

Protesting his uncle’s innocence, Darren adds: ‘Since the appeal case, DNA has come so far forward. I would like them to examine the procedure and how it was carried out.

Nowadays, it wouldn’t even have got to court – it would have been laughed out. Jimmy didn’t stand a chance.’

James Hanratty’s story appears on documentary The Guilty Innocent with Christopher Eccleston on Sky HISTORY, NOWTV and AppleTV.