Although it’s not uncommon for with their co-stars while filming, it’s rare for one actor to physically bite another – and even rarer for the director to film it and use it in the final cut.

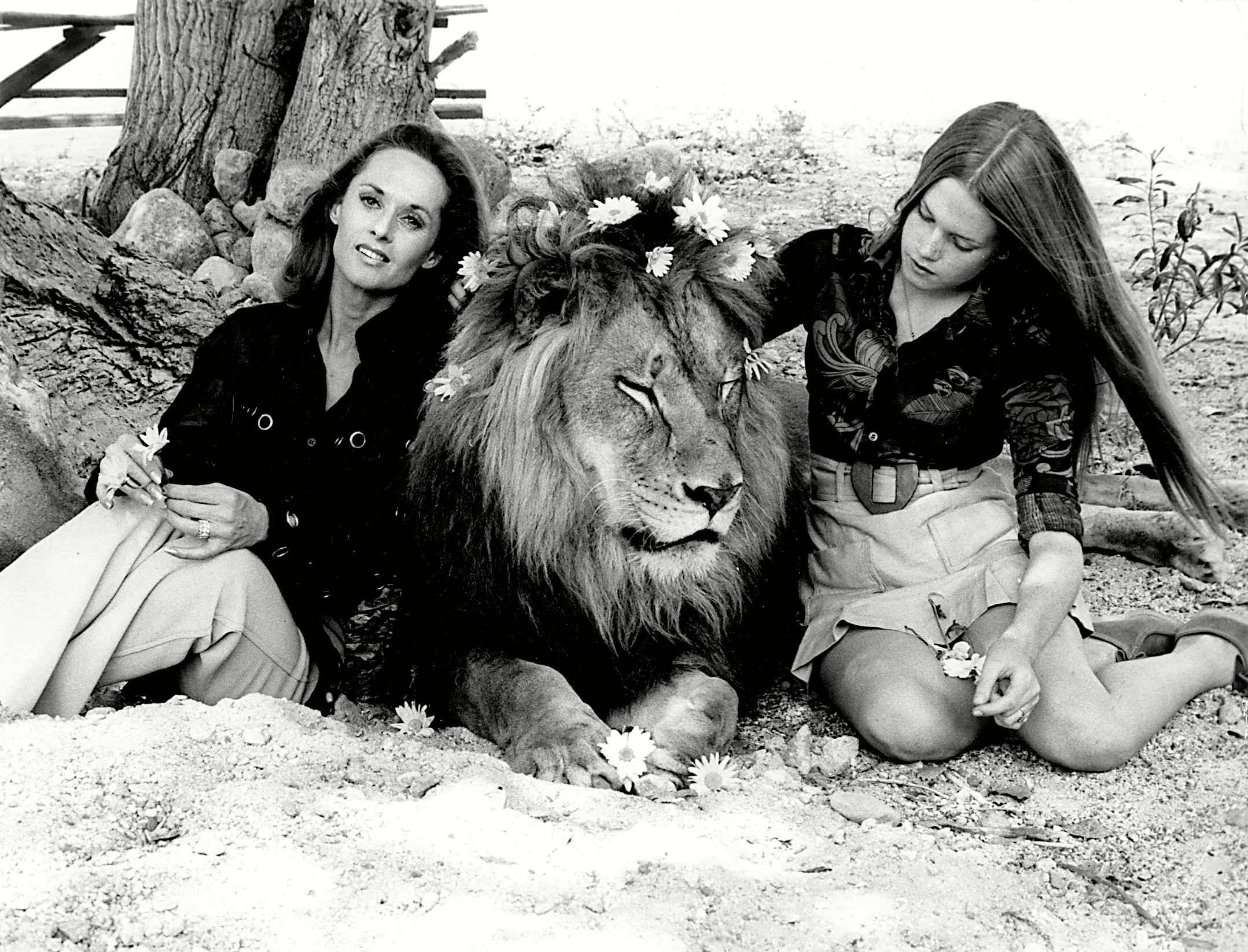

But that’s exactly what happened on the set of 1981’s Roar, a cult classic that was written, directed, and produced by Noel Marshall and starred , her daughter , Marshall’s sons John and Jerry Marshall, and a huge group of untrained lions and tigers, among other animals.

Thanks to the hundreds of injuries sustained throughout filming the movie – which was meant to display the natural behaviour of the animals so largely relied on them to generate action – including the cinematographer being scalped by a lion, Roar is widely considered to be one of the most dangerous productions in cinema history.

And how could it not be? When your castmates include 71 lions, 26 tigers, a tigon, nine black panthers, 10 cougars, two jaguars, four leopards, two elephants, six black swans, four Canadian geese, four cranes, two peacocks, seven flamingos, and a marabou stork; diva moments are more likely to end up with someone in the hospital than the tabloids.

Originally met with mixed reviews, the film has gained a second life recently thanks to renewed interest in the bizarre (and often gory) details of what the cast and crew, who lived among the animals during filming, went through to make it. Tippi Hedren, notably , has also made headlines lately as that the actress, 94, is ‘unable to remember her career’ due to advancing dementia.

This has inspired fans to reflect on the actress’ bizarre Hollywood life, which included an infamous incident in which Alfred Hitchcock tied birds to her. But that’s nothing compared to what she went through filming Roar, which has inspired a lot of dark jokes online that perhaps it’s for the best that Hedren doesn’t remember all the details of her career.

Hedren and Marshall first came up with the idea for Roar in the years following the disastrous fallout from Hedren’s entanglement with Alfred Hitchcock, who directed her in and Marnie; films that skyrocketed her to stardom. When Hedren denied the film auteur’s sexual advances he blacklisted her in Hollywood, threatening to ensure she never worked again. She wrote in her memoir: ‘I was never offered another role as deep and challenging as the two I did for him.’

Even so, she continued to find some work, ending up in Mozambique alongside Noel Marshall for the filming of Satan’s Harvest in 1969. There, the couple visited a house that was occupied by 30 lions. As they took in the big cats, Marshall, as Hedren recalls, uttered the words that would ultimately lead to 11 years of bloodshed and financial devastation: ‘You know, we ought to make a movie about this.’ In need of a way to prove that she was more than Hitchcock’s muse, Hedren agreed.

The couple decided that they’d live among the animals to earn their trust. So, upon their return to the States they began raising lions in their LA home. John Marshall later that, ‘We had this one neighbor that kept turning us in. We had a routine. Whenever the doorbell rang at seven o’clock in the morning, you knew it was animal control.

‘So Dad would answer the door, and Tippi, Melanie, and I would take whatever animals, whatever lions and tigers we had at the time at home, and we’d throw them over the fence. Our house was on a hill, and the house below us liked us. So we’d throw all the lions over the fence, and we’d be in our pajamas, climbing over the fence to keep them quiet.’

Eventually, the family was forced to move their animals out of the suburbs. They built a compound in Soledad Canyon, planting thousands of cottonwoods and Mozambique bushes and damming a nearby creek to create a lake. With their sanctuary prepared, they populated it with an ark’s worth of exotic animals. It eventually became one of the largest private collections of big cats in the world.

Filming began in 1970, meaning Griffith was just 13 years old. Hedren details the disastrous process, which took place over an unbelievable 11 years, in her memoir, painting a vivid picture of childlike idealism combined with a reckless devotion to a concept.

The plot of the film follows Hank (Noel Marshall), a wildlife preservationist, and his family who share their African home with countless lions, tigers, cheetahs, and other exotic creatures, ultimately resulting in a series of tense encounters and general hijinx. If you set the plot in LA instead of Africa, the film would essentially be a documentary of a very real family genuinely living among animals, that’s how loosely any narrative is truly adhered to.

The movie features several bloody run-ins between the human family and the animal characters, many of which weren’t simulated. Indeed, Marshall left the camera rolling during multiple instances of animals attacking human actors, meaning that a lot of the blood on screen is 100% real – as are the screams of terror. When you decide to try to teach a veritable safari of wild animals Stanislavsky, it’s unavoidable that some teeth will be bared, or as Hedren recalls about working closely with lions: ‘Being bitten is inevitable.’

One notable instance includes Tippi Hedren being picked up and thrown by an elephant, which resulted in one of the most memorable scenes in the movie and Hedren ending up with a broken leg.

Given that the animals were largely untrained, actors often provoked them to elicit responses, increasing the chances of attack. Marshall running full speed at a lion hoping it would give chase and Hedren covering her face in honey so another would lick it off are just two examples of the lengths they were willing to go to. Marshall, who reportedly had an explosive temper, would force the other actors (his wife and children included) to sit among the animals for hours at a time in hopes that the animals would do something that could be used.

The results were a gruesome list of injuries, with an estimated 70 members of the cast and crew sustaining an injury at some point while filming. These include Melanie Griffith’s face getting mauled, which required plastic surgery, Hedren contracted gangrene at one point and needed skin grafts at another, and Marshall, who was mauled repeatedly, contracted blood poisoning from his injuries and at one point nearly lost a limb.

The cinematographer Jan de Bont, who would later go on to direct films like Speed and Twister, had his scalp torn off by a lion, an injury that required hundreds of stitches to repair. De Bont, as certain as Hedren and Marshall that the concept of the film was revolutionary, returned to work shortly after the incident.

While all of this may sound like the makings of a truly chilling horror movie, the film is actually a comedy, though the tone it strikes is too strange to easily classify as anything familiar. Notably, the animals are credited as actors and writers, and with names like ‘Cherries’ and ‘Robbie’ there’s an overwhelming sense that those involved in Roar had a naive view on the reality of wild animals.

Hedren reflects on the injuries in her book, admitting that she sometimes had reservations about Marshall’s willingness to risk the wellbeing of his wife and children. She ultimately concedes that she ‘was into it every bit as much as he was,’ and calls those 11 years an ‘obsessive, addictive drama.’

Marshall, for his part, had a lot to lose. He was a producer on the smash hit The Exorcist and used that money to finance the film, which he originally estimated was going to cost $3million (£2.4m approx) to make. It ended up costing $17m (£13.4m approx) and forced the family to sell their homes and Marshall’s commercial-production company went bankrupt. By 1973 the cost of feeding the crew and the animals was $4,000 (£3151.04) per week.

In 1975 Marshall said in an interview with The Montreal Gazette that: ‘You get into anything slowly. We have been on this project now for five years. Everything we own, everything we have achieved, is tied up in it. Today we’re 55 percent complete. We’re at a point where we just have to do it.’

To make matters worse, the dammed lake burst in 1978, flooding the property and causing millions in damages, even stranding several crew members and allowing several animals to escape. The flood reportedly caused upwards of $3m (£2.4m) in damages.

So, after all of that catastrophe, was it worth it? Financially, no. The film only made $2m (£1.6m) at the box office, a meagre 12% of what it cost to make. Hedren and Marshall split shortly after and Marshall died in 2010, reportedly having spent years recovering from the injuries he sustained while filming Roar.

As for the fate of the animal actors, who the proceeds from the film were meant to benefit, they remained on the property which soon became the Shambala wildlife preservation run by the Roar foundation, which Hedren founded in 1983. The preserve is still there to this day.

The movie’s message. reiterated throughout with childlike insistence, is that the only thing preventing humans and beasts from coexisting peacefully is fear and misunderstanding. If animals are treated like peers, the movie seems to say, they’ll return that respect. But Roar’s message is so severely contradicted by its own production process that it collapses in on itself, coming off like a smile forced through a mouth full of blood.

Today, reevaluated through the eyes of modern viewers, the film is a monument to a specific kind of hubris that was characteristic of Hollywood at the time: the idea that anyone and everything was malleable in the hands of the cinematic impulse, even wild animals.

John Marshall, who was bitten multiple times throughout production, said of the movie, ‘Tippi and Melanie kind of want to forget about the whole thing. I still get nightmares when I watch Roar, so I don’t see it too often.’